When I saw the call for papers, I submitted a proposal titled “The Anthropological Dimension of Free Software: a Philosophical Argument” as you can see in the announcement in the program.

Anthropology is the study of various aspects of humans within past and present societies. There are many cases one can make for Free Software but I believe if one is an advocate for or an opponent of Free Software ultimately depends on one’s idea of human beings – or anthroplogy.

I have to admit; sometimes I use Google and Google services.

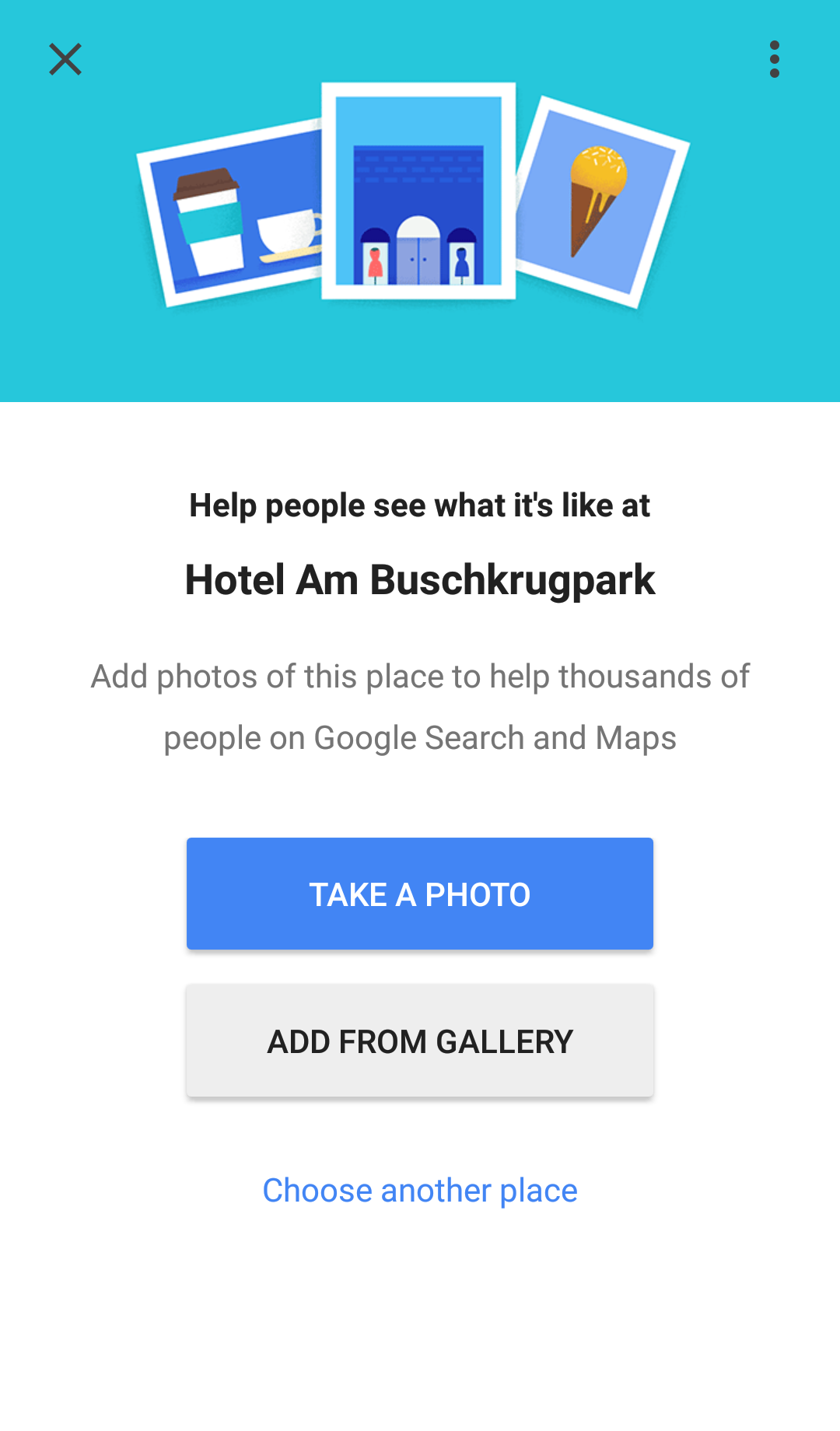

We are having a family dinner in a nice restaurant, the food is marvelous, and I take out my cell phone and take a picture of the antipasti. When we are ready for dessert my phone vibrates, there is a notification from Google asking me to contribute my photo to the collection of the restaurant’s photos on Google maps and comment on the restaurant.

You all know what’s happened. Google knows my location, my photos are geo-tagged and uploaded to Google photos, Google uses this information to ask me for more information – and if I share my photo on Google maps and rate the restaurant, then I further contribute to Google’s world-wide knowledge. I will not focus on privacy issues but on the aspect of sharing. When asked, it is a reflex for many people to help. They freely give their information to Google without realizing that Google does not reciprocate by making this information available under a free license but controls who gets access to this information.

Sharing – in my opinion – is one of the most important aspects of the Internet economy. However, multinational companies ask for their users’ data and contributions to advance their own business interests, to improve their products or to enhance their services. However, they regard their users’ contribution as their property without any obligation to share these contributions under an open license.

Anthropologically speaking, there are some basic conditions of human behavior. One is to help when asked. Google – and other Internet companies – are using or abusing this anthropological pattern of human behavior to skim information and to cage it in and release it whenever it suits the company’s interest. Users are made unpaid collaborators who share freely but their sharing is not reciprocated. Google’s operating system Android is based on Linux, Free Software developed and maintained by a community, but Android is boxed in and packed in a way that it only develops the full user experience when tied to Google services.

A quick note about myself, I studied computer science and theology, so I approach the topic of Free Software also from a theological, i.e. anthropological and ethical perspective and not from an economic perspective.

When an organization – which also applies to a church – attempts to introduce free software, the focus quickly shifts to economic arguments that free software is better, is safer and more secure or cheaper and more efficient.

All of this may be true in general, but it is always difficult to prove this in an individual case when the transition to Free Software is planned. There are studies proving the superiority of Free Software and counter-studies prove the opposite. The case for or against Free Software is based on economic assumptions. I am not an economist, so I will focus on the ethical dimension of Free Software. When we discussed the IT strategy of our church, the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland, an organization with 2.9 million members in more than 700 parishes, the decision to migrate our IT infrastructure to systems which run Free Software was mostly based on economic reasons but I am happy that our synod also considered the ethical dimension of the decision.

One can – and must – also discuss the business case of Free Software. Which is the business model when it comes to the creation, distribution and maintenance of Free Software? Which are the services that are paid for? What does this mean for the programmers, developers and maintainers? How are free-lancers being paid when they yield the rights of their work to the community? How are volunteers being rewarded? Does the distributed structure of software development of Free Software lead to permanent workers being laid off in favor of free-lancers doing their jobs? What are the workers’ rights – these are questions that need to be addressed as well – as it was done in the ATTAC Summer Academy this year in Düsseldorf.

As a theologian, I have learned to look behind the curtain and analyze the anthropology and the worldview or ideology that lie behind certain social or economic decisions or processes.

“It’s the economy, stupid” is an American political catch phrase coined by Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign. When we talk about Free Software, it is not about the economy but about our worldview or our understanding of human beings which leads us take sides in favor of Free Software. I am not negating that decisions to use Free Software for certain projects are based on an economic analysis but it is important to me that the overall question regarding Free Software is based on our worldview and anthropology.

“It‘s anthropology, stupid” I might rephrase the catchphrase when applied to Free Software.

When we talk about free software, we implicitly have a certain idea of human beings in mind. Software is not a material good; it can be copied and shared without loss. When we pass software on to others it does not diminish or become less, so we can give it away it freely. Or we can attach conditions to it. Who do we share software with? And how do we share? Or do we refrain from sharing at all? If and how we share software also tells a lot about ourselves and who we are. Is egotism or altruism the basis of our being? What is our idea of a human person? Free Software is an interesting test-case. Of course, the same would also apply to Open Educational Resources (OER), Open Data, Open Access: The key question is: do we share and how do we share?

Please bear with me if the following points are just some thoughts which need to be elaborated further but for lack of space and time I have to be short.

The definition of Free Software as offered by the Free Software Foundation – is not only a technical description, besides the technical dimension there is also an anthropological dimension to it. Even if you are familiar with this definition, I will run through it and comment on some points.

- The freedom to run the program, for any purpose.

Placing restrictions on the use of Free Software, such as time („30 days trial period“, „license expires January 1st, 2004“) purpose („permission granted for research and non-commercial use“, „may not be used for benchmarking“) or geographic area („must not be used in country X“) makes a program non-free.

- The freedom to study how the program works, and adapt it to your needs.

Placing legal or practical restrictions on the comprehension or modification of a program, such as mandatory purchase of special licenses, signing of a Non-Disclosure-Agreement (NDA) or – for programming languages that have multiple forms or representation – making the preferred human way of comprehending and editing a program („source code“) inaccessible also makes it proprietary (non-free). Without the freedom to modify a program, people will remain at the mercy of a single vendor.

The freedom to run a program for any purpose and the freedom to examine and modify the source code can be associated with the anthropological condition that human beings are curious and are natural born explorers. In the digital age, exploration is no longer restricted to physical spaces and places in the natural environment but to virtual environments e.g. code. These freedoms directly appeal to human curiosity.

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor.

Software can be copied/distributed at virtually no cost. If you are not allowed to give a program to a person in need, that makes a program non-free. This can be done for a charge, if you so choose

The freedom to make copies and share them with others resembles the Christian commandment “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Mt 22,39) or more universal, the golden rule applied to how we deal with code. The Golden Rule or law of reciprocity is the principle of treating others as one would wish to be treated oneself. It is a maxim of altruism seen in many religions and human cultures. Thus service to others is characteristic of Free Software

- The freedom to improve the program, and release your improvements to the public, so that the whole community benefits.

Not everyone is an equally good programmer in all fields. Some people don’t know how to program at all. This freedom allows those who do not have the time or skills to solve a problem to indirectly access the freedom to modify. This can be done for a charge.

This freedom aims at the common good, Free Software also serves the community and society as a whole and not only the advantage of individuals.

Without claiming the Free Software Movement as Christian, the above definitions of Free Software are an appeal to the Christian churches to commit themselves to further the cause of Free Software because Free Software as it is defined by the Free Software Foundation Europe has a great affinity with the Judeo-Christian idea of humankind.

Advocating Free Software is a consequence of one’s worldview and one’s idea of human beings

If the human calling is to be altruistic then sharing and working for the common good are mandatory.

“Omnis enim res, quae dando non deficit, dum habetur et non datur, nondum habetur, quomodo habenda est” (“For if a thing is not diminished by being shared with others, it is not rightly owned if it is only owned and not shared.”)

This quote of Augustine who was a bishop in the fourth century is taken from his book “De Doctrina Christiana” (“On Christian Doctrine”) and relates to teaching so Augustine can rightly be seen as an early advocate of Open Educational Resources (OER) but Augustine‘s concept of ownership and sharing can also be applied to other immaterial goods: Open Access, Open Data and Free Software can be deduced from Augustine‘s teaching.

In the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5,41f RSV) Jesus says:

“If any one forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles.

Give to him who begs from you, and do not refuse him who would borrow from you.“

And I would like to update:

“And if someone asks you to give him your source code, so publish it.”

Theologians argue whether the Sermon on the Mount refers to a new world which is already a reality for believers but not yet visible to others, whether it is a utopia or whether it is a program to change the world and a plan for a just society.

I want to open the question of the correct interpretation of Sermon of the Mount a little and rephrase it: What is the idea of humankind and the concept of society of those who are actively engaged in promoting Free Software, for those who practice code-sharing

“And if someone asks you to give her your source code, so publish it.”

Now we could start a workshop and everybody is sharing their visions, beliefs and experiences. Whether we feel committed to humanism and to the values of the Enlightenment, whether we are guided by the Judeo-Christian tradition, or we are adherents of Socialism – and I know this list of wordviews is not complete – or whether we are women and men of good will who simply seek to work for a just society, despite our differences in our worldviews we could agree on the altruistic value of sharing in our respective anthropologies.

However, there are worldviews or ideologies which do not agree on this and are not compatible.

Liberalism and Capitalism contradict the basic principles of Free Software

Conversely, one can also ask: What are the ideologies, anthropologies and economic systems which contradict the principles of Free Software?

For example, take economic Liberalism and Capitalism:

If this basic assumption about human nature holds true

„Homo homini lupus” („A wolf is man to man”)

then human egoism is the driving force and the individual pursuit of private gain the basis of society and society itself becomes a „bellum omnium contra omnes” („a war of all against all”).

The economic Liberalism as exposed by Adam Smith, proceeds from egoism as a driving force of the economy. In „The Wealth of Nations“, he writes:

“By pursuing his own interest he [one] frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it.”

According to Smith, the pursuit of one’s own economic advantage is the basis of all economic activity. Commerce – economic interaction – is driven by the individual’s egoism and not by a desire to promote the common good or what is in the best public interest. What does this mean for a society if its members are motivated by their own egoism? At this point, Smith postulates an “invisible hand” which controls all activities invisibly and guides all egoistic behavior to serve society as a whole. If everybody’s self-interests are pursued then it is ultimately the best for all. The sum of all egoistic behavior is led by an invisible hand to promote the common good of society.

Thus Smith’s assumption of egoism as a driving force is the basis of economic Liberalism and Capitalism.

Postulating an “invisible hand” that guides all activity to ultimately serve the best interests of society as a whole has almost a theological quality and could be understood as a statement of faith. Nobody likes to be called an egotist in front of others – even if we are one – so Smith’s invisible hand also serves as an excuse to make egoism more acceptable. If I pursue my own self-interests, I am helping to promote a better society because if all self-interests are added up it is for the best for society as a whole. Being egoistic becomes a service to society.

If self-interest is the driving anthropological force, then capitalism becomes the socio-economic model for society. This has implications for how we deal with information. Information is not freely shared but collected and hoarded and only passed on if it serves the self-interest of the economic players, individuals or companies. The so-called vendor lock-in is an example how data are boxed in and basically used as hostage and leverage. Sorry, there is no Free Software under this paradigm.

From the Mayflower to Google, Microsoft and Facebook and to Wikipedia, Creative Commons and the Free Software Foundation

Is it an accident of history that the world’s biggest IT and Internet companies are located in the United States? Google, Microsoft, Apple and Facebook were founded in America before they started to dominate the world market in their respective fields. In addition to these economic global players, the biggest not-for-profit foundations are US-based, too. Wikipedia is the largest online encyclopedia of free knowledge, Creative Commons is the world’s leading framework for free licenses and the Free Software Foundation, a champion of Free Software, was founded in America, too. Is it a coincidence that the land of capitalism is also home to idealists who have started the foundations which shape the Internet, too?

The pursuit of happiness as mentioned in the US constitution may lead to pursuing economic success for one’s own benefit or foster idealism which focuses on the common good. Both is in the founding genes of America. The Mayflower brought both idealists – Puritans who wanted to start a new society – as well as profit-oriented entrepreneurs and adventurers to the New World. Looking at the first 100 years of New England history, we find two conflicting factions, the Puritans wishing to farm the land cooperatively, and entrepreneurs who migrated to the New World to seek wealth and success.

Today’s dominance of the USA is a result of a mindset that evolved in England and its colonies, but not in Spain, Portugal or France and their colonies: the Puritanism of the 17th century. The American sociologist Robert K. Merton, to whose doctoral thesis Science, Technology and Society in Seventeenth Century , I owe the basic idea for this lecture, proves that Puritanism led to a mindset in 17th century England that led to the emergence of modern science and to inventions and progress in technology, which were the basis for the upcoming industrial revolution. Even though Puritanism started as a religious movement, it changed the English society as a whole. Applying their faith to the world, Puritans strove to serve others and society and to study nature. Merton counts more than 100 Puritan movements, sects and factions. Puritanism was multi-facetted and divergent in the interpretation of the Christian faith but the emphasis to serve others, do good deeds and discover nature and advance knowledge was common to all Puritan strands and common in society as a whole. Puritanism was a lot more than what most people associate with Puritanism today when they think of Puritan bigotry and narrow-mindedness. Although Puritanism is a strand of Protestantism and thus a religious movement, it was also a movement advancing science and knowledge beyond religious boundaries and – according to Merton – in this aspect independent from one’s individual beliefs. Advancing knowledge and advancing the common good were widespread attitudes at that time. In this aspect, Puritanism is a predecessor to the Enlightenment. Whereas Enlightenment focusses on human emancipation from authorities by reason, the Puritans began to share their ideas because advancing knowledge was a service to others.

Merton characterizes this attitude:

„Free communication between the inventors, a system of cultural values which places a high estimation upon innovation and to accumulation of knowledge, all which is at the ready disposal of the would-be inventors”

This development in the England of the 17th century and in its North American colonies – the emergence of modern science and technological progress – was possible because of the mindset of free sharing and because of new means of transportation and communication: scholars were able to attend conferences, to circulate papers and to organize themselves in societies, such as the Royal Society of Science founded in 1660 and share their ideas, their knowledge freely.

Free sharing became the transmission belt of scientific progress. This orientation can best be described by the term “communalism”: all scientists should have common ownership of scientific goods (intellectual property) in order to promote collective collaboration.

Although many view the United States as an example of capitalism per se, there is also the American tradition of “communalism” – often referred to as communism – the orientation of one’s action to serve the common good alongside Capitalism and economic Liberalism.

There were two types of people on the Mayflower, some were coming to the New World to seek a better society and some were adventurers and fortune seekers. We are entering the global information society and we have to decide which tradition will gain the upper hand. In 17th century England, new means of transportation and communication developed. In the 21st century, we have means of transportation and communication that generations before us could not have dreamed of. However; not only communication and transportation were necessary for the progress but the sharing of information. Are we sharing information as freely as in the 17th century? I know that search engines are different from encyclopedias but I will use this as an example nevertheless. The question is who will keep our knowledge available and accessible: Google, a share-holder owned for-profit company whose search engine makes its users surrender their data and demanding control of their data or Wikipedia, a free online encyclopedia to which anyone can contribute, which is controlled by a community open to anyone and access to the accumulated knowledge is granted under a free and open license to anyone.

Is “Do not be evil” sufficent?

Google is often projecting itself as a do-gooder, “Do not be evil” is the company motto but this is the reality, too: Users are asked to tag photos and place them on maps, geo-information in smartphones is skimmed and processed, searches are correlated and used for predictions, user data are collected and used to enhance Google’s economic goals and business model. User Data are monopolized and access to them is controlled by Google and granted on Google’s terms. No Open Data license for user data, but control by Google.

The same applies to code: Android’s basis is Linux, a Free Software operating system but Google has enhanced Android by adding components so that full functionality is no longer provided as Free Software. Google used Free Software and boxed it in a way that it is now Google-controlled Non-Free Software.

When I had the chance to talk with a Google representative, I addressed these issues and asked him why user data gathered by Google are not placed under free data licenses or additional developments to Free Software are not placed under a Free Software licenses, he did not really understand my point. He pointed out to me that Google’s services are (usually) offered at no charge and thus Google is making a contribution to the common good. In reality (or in my point of view), Google controls the information, pursuing its economic self-interest – and magically as the invisible hand of Adam Smith – this pursuit of self-interest turns into the best for the society. Some might believe it, others don’t, everybody must make up their own mind.

Sharing is the Watershed for the Development of the Information Society

Egoism or altruism? What is the basis of the information society and its economy: for-profit orientation or public-interest orientation? Which way we decide depends on our anthropology, and on the social and economic system, which goes in hand with the anthropology. What is our vision for the information society in which we are and will be living in the future?

In the development of the information society, handling of information is the crucial question. egoism or altruism can be deducted by the way we share or do not share. Do we share information, knowledge, teaching and learning tools, code, algorithms, data freely or do we control them, hide them, hoard them, box them in and pass them only to others if we receive monetary compensation?

Open Access, Open Educational Resources, Free Software, Open Data – these movements could shape the information society or will they succumb to multi-national stake-holder companies which control and monetarize information?

The biblical idea of humankind and Christian social teaching – as I understand it – lead to sharing information freely. The same could be said for humanism or socialism and other worldviews. Of course, these worldviews include utopias, and one may well argue that capitalism has a more realistic idea of humankind than other worldviews.

Maybe, we need a utopia as a goal to strive for even if we never fully reach this goal.

We see the success of Google but there is also Wikipedia, most desktops run Microsoft operating systems but there is also Linux. Everyone has the choice, not only between operating systems or search engines, but also between different ideas of humankind and worldviews.

“And if someone asks you to give him your source code, so publish it.”

How do we respond?

Talking about Free Software? – It’s Anthropology, Stupid.

Please note: This version of my presentation at the FSFE Summit 2016 is without footnotes which give credits for citations. Some reference can be found in the first German version at https://theonet.de/2016/08/26/freie-software-auch-eine-frage-des-menschenbildes/

Ein Kommentar zu “Free Software? – It’s Anthropology, Stupid”

[…] ← Was würde Jesus zu Freier Software sagen? Free Software? – It’s Anthropology, Stupid → […]